Uphold Wang Jingwei Thought

On "Poetry, History, Memory: Wang Jingwei and China in Dark Times" by Zhiyi Yang

I recently read Poetry, History, Memory: Wang Jingwei and China in Dark Times by Zhiyi Yang (University of Michigan Press, 2023), a biography of the most damned person in modern Chinese history. Wang Jingwei’s lives were many. He was the Kropotkin-reading member of the underground Tongmenghui who attempted to assassinate the Qing regent Prince Chun, and whose unrepentant confession of guilt at his trial so moved the Qing officials that they spared his life. He was the confidant and heir apparent of Sun Yat-sen and leader of the left-wing faction of the Guomindang who eventually lost the power struggle for party leadership to the right-wing Chiang Kai-shek. And ultimately he was the collaborationist traitor who led the Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China (RNG), a Japanese puppet state. In all of those lives, he was a widely acclaimed poet of Chinese classical-style verse. The poetry, Yang argues, is the key.

Had Wang Jingwei died before his flight from the wartime capital of Chongqing to Hanoi in December 1938, where he and his followers in the “peace movement” entered negotiations for a peace settlement with Japan, he would’ve been memorialized as a revolutionary intellectual patriot, a founding father of the Republic of China. Instead, he faces damnatio memoriae, complete erasure from both Nationalist and Communist postwar historical memory. His name is synonymous with treason. He is a totally haunted figure. The statues of him that do exist in China depict him and his wife kneeling in humiliation, inviting the viewer to kick and spit on his likeness. Wang was an accursed poet, though not in the sense of crime or insanity or drug abuse—he was widely known to be handsome, charming, charismatic, and morally upstanding. It was those “heroic” characteristics that make his fall from grace all the more striking. Seemingly anticipating his doomed posthumous reputation, on his deathbed in Japan during the final months of the war he asked his family and followers not to publish his speeches or essays—only his poetry.

If Yang’s reading is to be believed, Wang Jingwei was more conflicted about his decisions and his role in the fate of China than he could let on in his speeches and other writings. Wang and his followers saw their own collaboration as an act of patriotic self-sacrifice for a nation faced only with bleak options. They knew, for instance, how shameful it was for them to lose the city of Nanjing to invaders, only to then return after the mass rape and slaughter of their compatriots and use the pretense of “anti-imperialist Pan-Asianism” to establish a Japanese puppet regime there. They were no doubt aware of the irony of having a regicidal assassin take charge of it. It was a regime of poets, doomed elitist poets who spoke to each other in the pages of literary magazines through the coded language of ci poems. In these litmags the poets tried to transform the image of their regime, to interpret their present circumstances, and to imagine their fate—or to simply look away from the yawning abyss beneath their feet. They were poets of impotence and delusion, weary of history, tortured by déjà vu.

Whatever altruism motivated Wang Jingwei’s decision to collaborate, it was a tragic altruism, the sort of high-mindedness that inevitably leads to stupidity and disaster. Wang misjudged Japan’s willingness to negotiate and China’s ability to fight a protracted war when it seemed hopeless. He wrote better lyric songs than both Chiang and Mao, but he made worse decisions. His romantic self-image and “democratic,” “constitutionalist” principles were utterly detached from the brutal reality of the Japanese conquest. His regime was hated by the people. Curiously, Wang’s poetry became lighter and more tranquil as the prospects for the RNG deteriorated, a trend that becomes especially pronounced in the summer of 1942 after the US Navy’s decisive victory at Midway—as if looming defeat meant he was finally released from the duty to make history, to martyr himself. The catharsis of the wrong bet. By fall 1943, the regime poets of Nanjing were spending more time than ever drinking and versifying. By the end of 1944, death came to Wang in the basement of a Japanese military hospital, after an extended bout of illness caused by a previous assassination attempt, as a blessing. And then, the final collapse of his life’s enterprise, the complete damnation for him and his followers, the triumph of communism, the next cycle of rises and falls.

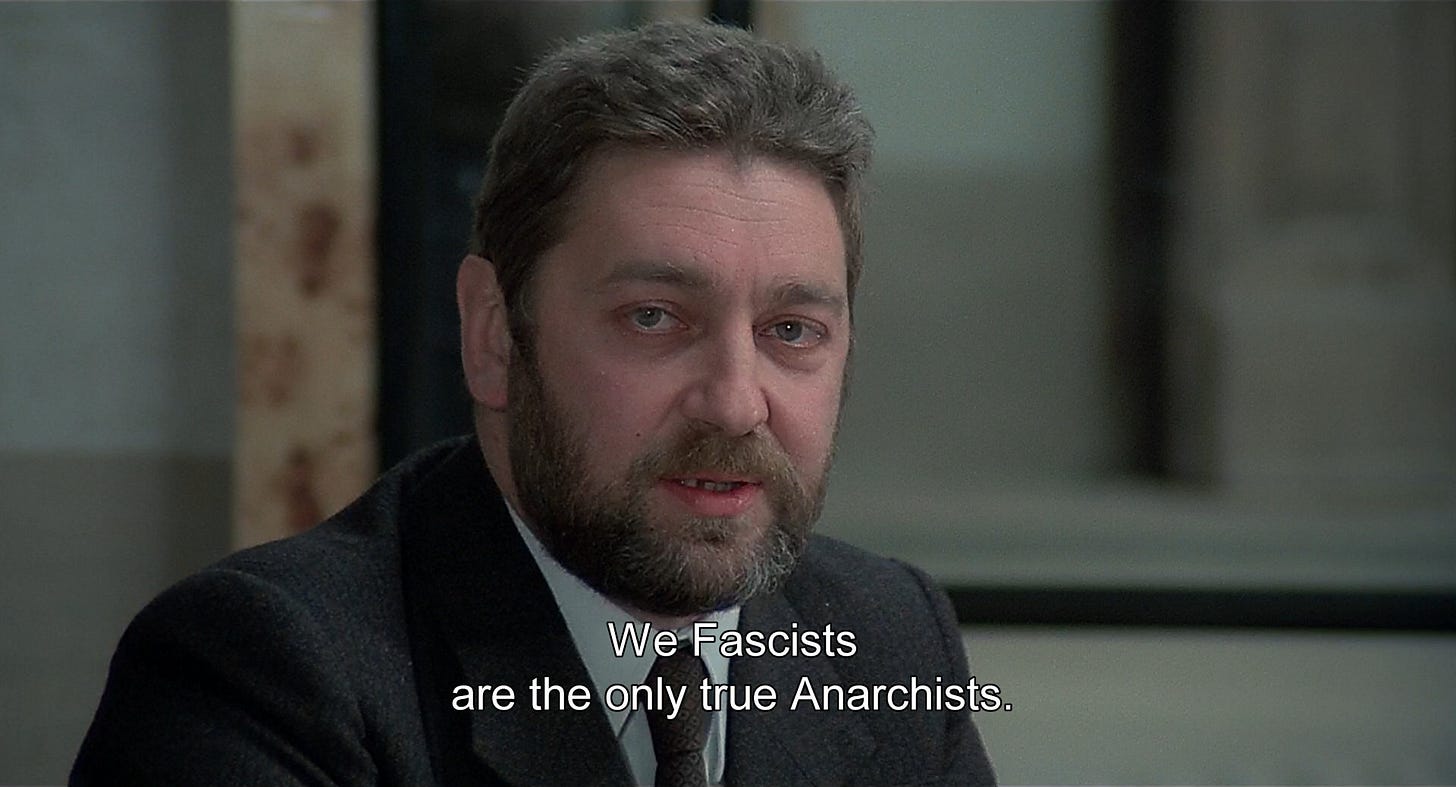

Ironically, Wang Jingwei’s complete erasure from official Chinese cultural memory means that he can live on in a sort of paranoid, repressed form through his poems and accursed likeness. Many of his poems, particularly from his younger, “politically-correct” days, remain popular in China, though typically in ways that somehow forget or disavow their author. He apparently continues to top internet lists of the most beautiful figures of Chinese history. There’s no one more fascinating than the damned. Yang’s book asks: How much can we trust a poet’s self-portrait? And what is the relation of poetic truth to historical truth? These questions are particularly salient when reading the poetry of fascists and collaborators who see their own treason as patriotism, in China and beyond, regardless of whether they turn out to be the winners or losers of history.

Nice