Worst Boyfriend Ever

Subjecting the pseudonymous libertine to a Voight-Kampff test of literary self-awareness

I saw on Twitter that Worst Boyfriend Ever was in New York City. For the past year I’d watched him blow up on Substack, filing dispatches from a van as he drove across the country trying to fuck as many Asian girls from Hinge as possible. That winter he took the project to the Philippines and Japan. The prose is fast, vulgar, diaristic, deliberately unrefined, and saturated in shameless exaltations of cruelty and sexual violence.

He was clearly repulsive. But could he be a serious writer? And what would it take to make serious writing out of that?

***

In a certain corner of the internet, Worst Boyfriend Ever is a kind of folk hero. He is envied, eroticized, mythologized, and framed as destiny. What follows are artifacts of that fantasy circulating among men online.

Delicious Tacos, a leading confessional male internet sex writer, feted by both the Sovereign House and Columbia MFA crowds, imagines the life he should have lived instead: driving a van, “fucking Chinese idiots,” blasting in them raw and leaving. Everything WBE says about women is true, Delicious Tacos insists, and he makes you mad only because you’re not living the life you should be living. “His crimes only make it more likely that a beautiful woman will love him in the future.”

The marginal blogger known as Toxic Brodude reviews Worst Boyfriend Ever as if discovering a lost scripture. “He’s too eloquent in expressing himself, and too self-aware to be written off as a blundering fool,” Toxic Brodude writes, “I have no doubt this guy is tall, handsome, talented, and funny.” The real injury, he explains, is that WBE stands outside the literary industry only because the industry has been hijacked by “certain demographics.” If you were born male, then you’ve had a WBE period. He is all of us.

An editor at a small press, writing under the name MATTP969 in Strange Flows, describes almost releasing WBE as if recounting a near-miss with destiny. At first, he writes, he was skeptical. What changed his mind was meeting WBE in person, and only afterward reading the writing. He recalls telling him about his long-term girlfriend, and his relief when the great Casanova does not sneer but congratulates him instead. He then daydreams about future collaborations between himself, “the man who had nearly always chosen stability,” and WBE, the “folk hero who had made it his dharma to do the opposite.”

I knew I had to meet the man to see if he lived up to this ideal.

***

When I reached out, Worst Boyfriend Ever agreed to an interview. I mentioned this to my friend Nick Dove.

“Ugh. Disgusting,” he said. “I’m so sick of all this rapecore literature. I don’t want to be associated.”

“He told me to meet him at KGB.” I told Dove. “You should come with Jean-Baptiste.”

Jean-Baptiste is a French journalist we met in New York last spring. He’d come to write about Dimes Square and was working on a video project framed as a space alien’s study of human life. Now JB is back in the United States and crashing at Dove’s place in Jersey City. He read two WBE Substack posts and said he was interested in meeting the guy.

“Wait, Worst Boyfriend Ever is reading at KGB?” Dove asked the day we were supposed to meet up.

“Yes, he confirmed it with me today,” I said.

“He’s reading at the Easy Paradise open mic thing? How? That crowd is normie-woke. He’s gonna get booed off stage. I have to see this.”

So, Dove, JB, and I all went to KGB Bar to see WBE reading at the normie-woke open mic.

Inside the first-floor theater, I scanned the audience looking for WBE. Dove sent me a photo he had taken of him at the New Ritual Press party last spring. It showed a handsome but otherwise unremarkable white guy in his late twenties. I showed it to JB.

“This is our guy,” I told him. “Keep an eye out.”

WBE texted that he was across the street at a pizza place and sent a photo of his table. JB and I went to meet him. When we arrived, his own book was laid out in front of him, next to a slice of pizza.

“I recognized you from a photo Nick Dove took at that New Ritual Press party last spring.” I told him.

“I don’t know who that is.”

“You’ll meet him in a moment.”

I told WBE I’d been following his Substack for a while, that I’d read his account of cheating on his girlfriend, his van life, and his recent travels in the Philippines and Japan. I said I was interested in his following, and in how he’d convinced so many strangers to send him thousands of dollars.

“So, how have you been enjoying the fine women of New York City Hinge?” I asked.

“Actually, I haven’t really been using the apps lately,” he said. “I’ve mostly been meeting with women who message me first on Substack.”

“Are you making a lot of money from this?”

“Not really.” On his phone he showed me the Substack analytics on one of his recent posts. When he pulled up the Substack dashboard, he held his hand over part of the screen.

“Why are you doing that?”

“I don’t want to see the comments.”

“Right,” I said. “Your posts get a lot of engagement. I’ve read a lot of the commentary on your work. The Delicious Tacos piece is among the first that come up when I google your name. The Donald Boat one is the other, though that’s less flattering.”

“I didn’t read the Donald Boat piece,” WBE said.

“You probably don’t need to,” I said. “If I were to write a takedown of your work, I’d approach it differently.”

“How?”

“That’s what I’m trying to figure out.”

“How much of what you write is fiction? Or fantasy?” JB asked.

“Everything I write is true.”

“Of course. What is even worth writing, if not the truth?” JB mused as he began rolling a joint. “And to what ends does this truth serve?”

“I just write to be funny. I write whatever shit I think is funny in my notes app and then I refine the best stuff and publish it. I’ve only published like 1 percent of the stuff I write down.”

“You’ve cited Delicious Tacos as an influence,” JB went on, “Are there any other internet literature figures, or downtown scene figures who you consider influences?”

“Not really. I don’t really know much about most of these New York people. I just got here. The ones I do know of aren’t really my taste. I don’t think they’re that good. And Delicious Tacos is out in LA.”

JB glanced at me, as if to signal a bluff.

“As I’ve read your work,” I said, “I’m struck by the extent of the categorizing in the scenes you stage—race, age, app, costume, vibe, sexual role, emotional availability, flake status, novelty. It’s hard for the amateur psychoanalyst in me not to read this as a defensive taxonomy, a defense against replaceability. The women are typed and dommed into familiar scripts. They never get interiority, because the narrator interprets their desires in advance as desire for him. But on the other side of the scene is not a singular narrator, but another legible figure—a very common type of guy. Maybe the women read him more clearly than he suspects.”

“No, I’m not concerned about that. There’s only one guy doing this cross-country van thing. It’s performance art. No one else is living this life.”

“I respect the confidence. But I mean, certainly this would be something that could be unwittingly expressed. You know, that someone’s own prose could betray them.”

“I’m not worried about that.”

“Do you have any scenes you’ve written that stage real power reversals? I mean scenes where the narrator is then interpreted, in a destabilizing way. Where the girl really has you clocked.”

He thought about it for a moment.

“Yes, I think so. You should read the piece “Forcing Myself on a Harvard Girl” if you haven’t already.”

“Great, I will do so tomorrow. As for now, we should probably get back to KGB for your big performance.”

***

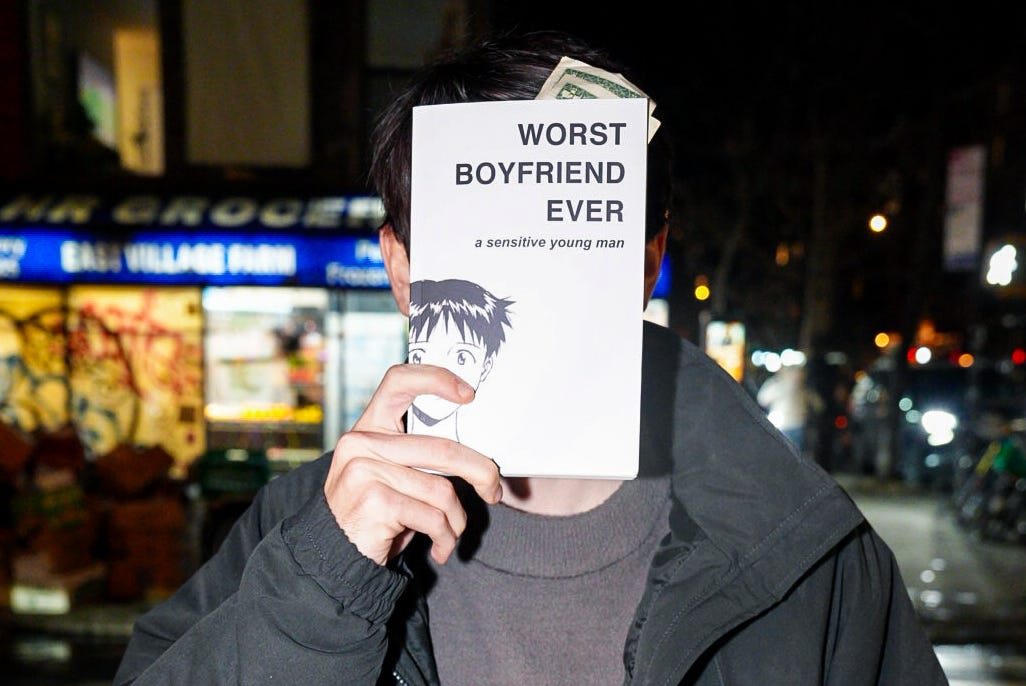

Back inside KGB, I sat next to Dove and JB, and we watched a series of perfectly decent normal open mic acts: mostly musicians, some clowns, and so on. The emcee had a funny haircut and danced around on stage a lot. When it was WBE’s turn, he read a piece called “Slut Review: Katie from Hinge,” which is the first chapter of his eponymous self-published novel. Hiding his face behind his own book, with its cover illustration of Shinji from Neon Genesis Evangelion, he began reading:

GF just sent me a scary text: “We need to talk. I just found hair ties under the bed that are definitely not mine. Did you cheat on me while I was gone? What the fuck. Please don’t ignore this.”

Yes. Yes I really did. Her name was Katie and she was insufferable.

I found her on Hinge. I re-downloaded Hinge as soon as you left.

Once I remembered you could filter by race, I stopped using all the other apps. Within a day I had over 20 relatively beautiful Asian girls in my inbox. Most of them were flakes, they always are.

But one of them was clearly looking to meet somebody. She had “looking for cuddle buddy/fwb” in her profile. She must have been new to the app because girls like this don’t last long.

She had a picture of herself wearing one of those black Japanese maid costumes and lyrics from a Radiohead song. I knew she was the one.

Our conversation became sexually explicit very quickly. The sunlight was streaming in through our huge windows, casting a warm glow onto the bed. I sent her a picture: You want to get fucked right here? She replied: Yes please…

The crowd was palpably confused at first, but after a minute people seemed to settle on treating it as satire, and the tension waned slightly. A few rows ahead of us, I spotted an Asian woman who was not having it. Dove took a photo of her reaction. The photo is washed in red stage light. You see her turning around, open-mouthed exasperation in sharp focus. Blurry in the background looms Worst Boyfriend Ever. There is a faint erotic intensity to the image itself that makes it uncomfortable for me to look at. We then watched this unwitting participant in the performance get up and say something we couldn’t hear to the emcee.

Suddenly WBE ended his reading mid-chapter, said he’d seen the lights, and ran off the stage and out of the building.

On the street I noticed a small group speaking Dutch, armed with cameras. It was KIRAC. They had come after seeing WBE tweet that he was reading that night.

WBE reappeared a moment later and said he’d just walked around the block. The KIRAC crew immediately gathered around him.

We went back inside. Dove left early. When JB and I left at the end of the night, WBE and the KIRAC crew asked if we would attend their film screening at Nightclub 101 on Wednesday, where WBE would now be reading. I said I’d try to make it.

In the car home, I debriefed with JB.

“He claimed not to know the New York scene, but he still agreed to an interview with you.” JB said.

“At some point he told me that he first heard about my writing from some girl in San Diego who told him that she only read two Substacks, his and mine.” I said. “What a weird detail.”

“Did you notice his shoes?” JB asked.

“No, why?”

“They were like, five sizes too big for him. They looked like Foot Locker clown shoes. I tried to get a picture, but you can’t really see them. And where were all the ‘bitches?’ I didn’t see any women approaching him, or vice versa.”

***

At home in Flatbush, I sat down to read “Forcing Myself on a Harvard Girl,” as WBE suggested. I read the piece with a specific goal in mind: to test power reversal as a formal diagnostic of narrative ability.

Confessional realism

What does WBE claim to be writing? I’ll call this “confessional realism.” Confessional in the sense that it’s written in the first person and centers around intimate, taboo material, and this exposure is meant to stand in for sincerity and vulnerability. Realist in the sense that these scenes are presented as literal accounts of real events and invite the reader to generalize from them. “Everything I write is true,” he claims. “He is all of us,” his fans claim. The narrator is reliable, they say, and his work describes reality—not just his own twisted mind.

WBE’s prose repeatedly claims omniscience about the minds and motives of the women he interacts with: certainty about their desire (“Do you like Neon Genesis Evangelion?... From that moment on, I knew we would fuck”), emotions (“She was a troubled little soldier for sure”), and stupidity (“She was stupid—so stupid”). The issue here isn’t that it’s mean or hateful to women. It’s that this omniscience produces a sealed-off narrator perspective, one that is emotionally invulnerable, undercutting the writing’s “confessional realist” posture.

A close call

WBE stages scenes full of moments where another mind could break through. Here’s one in “Slut Review: Katie from Hinge:”

I make just one tactical error in my performance. I’m trying to convince her to do some regular physical activity because that’s the only time I ever feel alive and I say:

“you know how most human interactions in daily civil life all feel kind of sterile and gay?” —

She tenses up at my usage of the word “gay.” I forget she’s a female college student on the west coast United States, fully indoctrinated, so I have to explain how I have no hate in my heart towards gay people (i don’t even believe in “gay,” but that’s another story) but I sometimes use the word “gay” in that 2012 way to mean “weird, unnatural, bad.” She doesn’t like that explanation either.

I’m trying to say you should go for a run, Katie. Move your body, it’s free dopamine, it makes you less depressed and insane. Maybe you won’t be so compelled to fuck random guys like me all the time, but all she hears is that I call things “gay” and gets The Ick.

Instead of allowing her reaction to stand as a perception of him (which would constitute a genuine power reversal), the narrator reframes her response as ideological indoctrination and generational cultural deficiency. The misrecognition is her failure to understand him, not the reverse. Her perception never becomes information about him, it becomes information of the shallowness of women and liberal culture, and evidence of why one must self-censor. It’s damage control.

As I’m reading this, I’m also thinking that the girl has him correctly clocked. It’s true that from this use of the term “gay,” he reveals a lot more about himself than he intends. There is clearly so much ideology present in “most human interactions in daily civil life all feel kind of sterile and gay.” She’s not wrong. She sees something real about him here, something the narration cannot accommodate. She sees it, the reader sees it, but the narrator cannot.

So, think of the power reversal here as a sort of literary Voight-Kampff test. It’s the only way to verify that the narrator’s mind-model includes other minds that occasionally can push back, correct him, or see him more clearly than he sees himself. Without that, everything he reports becomes suspect—not because he’s lying, but because he literally cannot register contradiction. At that point, the work slides from “confessional realism” into something closer to involuntary farce. Readers are no longer listening to the alpha male women-whisperer, they’re now watching a “retarded lolcow” stumble through the world.

Forcing Myself on a Harvard Girl

In “Forcing Myself on a Harvard Girl,” WBE meets a young Harvard-affiliated woman at her apartment in Cambridge after she has invited him for coffee or dinner, intending the meeting to last about an hour. He questions her, shows her a fictional story he wrote about drugging and having sex with her, and reveals that he has looked up her real identity. When she asks him to leave, he refuses, staying close and repeatedly pressuring her to kiss him despite her objections. As the situation escalates, he restrains her and tells her she has no leverage because he is physically stronger. She considers calling the police and attempts to involve a friend, but he continues to confine her. After hours of pressure, she resigns herself to continuing the encounter, and eventually, in order to make him leave, she agrees to kiss him. He then leaves and discovers that his van has been towed.

Of course, there is no such power reversal in this scene. What WBE seems to mean by “power reversal” is not a loss of interpretive authority but a moment of friction that interrupts the fantasy of effortless desire. Nothing in the scene allows the woman’s perception of him to become authoritative, not even for a moment. In fact, there’s even less of a power reversal here than in “Slut Review: Katie from Hinge.”

When I originally suggested that the taxonomic structure of his writing functioned as a defense against replaceability, it was a kind of speculative vibe hypothesis. Something like, I suspect that this guy categorizes to create structure and certainty, perhaps because he himself feels vulnerable around women. His whole persona and body of writing is about staying in control, which he naturalizes as part of the universal dom/sub script for how men and women act. Since this taxonomy never really turns its gaze back on the narrator—a glaring omission—one could suspect an anxiety about being typed and legible in this same way. But at the time, I was mostly just riffing.

From there, he doubled down on his sense of personal singularity. Ironically, the scene he then offers as an example of power reversal is one organized precisely around sexual replaceability: the Harvard girl has eight men texting her, a boyfriend, and a friend who nearly rescues her from him. His response is to imprison her until he secures a form of validation unavailable to the other men.

A real Casanova

Reading across his work, what is striking is the invariance of the scenes. The women are almost always younger, unstable, socially marginal, sexually inexperienced, or explicitly vulnerable. They are categorized, approached, interpreted, pressured, and finally either overridden or dismissed. When sex works, the scene ends in conquest. When sex doesn’t work, the scene ends anyway. It never ends in a new understanding.

This is not what a real Casanova’s archive looks like. A seducer who moves through a wide social field, courting women with real interpretive leverage, accumulates failures, embarrassments, misreadings—women who see through him. Here, those scenes do not exist. Either they never happen, or they cannot be written.

Or rather, selection precludes them. He selects—or is left with—encounters in which the distribution of power is already settled, filtering out women who might interpret him accurately (these women are then comfortably categorized as “flakes”). Because his art cannot tolerate a consciousness strong enough to look back at him, it never develops beyond the single trick it already knows.

***

I arrived late at Nightclub 101. I slipped in during a reading of a pornographic short story by one of the KIRAC people. Someone told me Worst Boyfriend Ever was in the back room behind the stage.

I went back there and found him chilling by himself. I noticed he was now wearing shoes that fit.

“Where’s JB?” I asked.

“Haven’t seen him,” he said.

“Did you read already?”

“Yes.”

“Did you finish this time?”

“Yes. And I read another thing I wrote today, a new piece that was even more misogynistic.”

“And the KIRAC movie, have they shown that yet?”

“Not yet.”

“What do you think they want from you, exactly?”

“Clout,” he said.

When I stepped out of the back room, I found JB in the audience and sat next to him. Then came the movie. The plot was typical for KIRAC: entrapment and humiliation of a minor right-wing internet writer. They staged a fake intellectual symposium as a pretext to expose the writer’s infidelity in front of his girlfriend. He had ended an affair with the niche Twitter e-girl Bimbo Übermensch, who had joined forces with KIRAC to get revenge. This writer they were trying to humiliate was a fascist occultist charlatan I really can’t stand, so I found myself rooting for KIRAC. But the humiliation never quite landed, and in the video Bimbo Übermensch looks disappointed by the reaction she ends up getting.

After the movie JB and I stepped outside to smoke. As we stood there, a large group began to gather—KIRAC, WBE, various Sovereign House orbiters and scenesters—drifting away from the venue as if by consensus. Someone said we were heading to KGB. Apparently, Nightclub 101 was quietly ejecting the whole group because of WBE’s reading.

Back at KGB, the KIRAC crew told me they planned to throw a party at WBE’s sublet in FiDi, where they would be filming e-girls for the launch of “Thirst Trap Magazine,” an internet platform they said would be “the next Playboy.”

***

So, what difference does it make that Worst Boyfriend Ever’s prose can’t grasp power reversal? What do you get when reciprocity is impossible in this particular form of hyper-immediate confessional internet writing?

Rather than a raunchy picaresque that exposes and ridicules the hypocrisies in contemporary dating, we get a solipsistic gooner power-trip. The prose has the formal structure of pornography: unilateral, controlled, fantasy-preserving. Serious writing in this genre tolerates interpretive loss and other minds.

And a power reversal happens anyway, between the narrator and the reader. As hard as the prose itself tries to avoid it, the narrator is still exposed by his own text. His “alpha” stance becomes comic. He thinks he’s reporting on women. But what you get instead is a case study of the man himself. The very thing meant to display mastery becomes proof of its absence.

maybe i'm just burnt out on the last two decades of feminist discourse but as a woman i found this way of analyzing a creep like this vastly more informative, insightful, validating, and encouraging than a hundred essays analyzing why his writing and behavior are misogynistic could ever be. sometimes, as a woman, the thing you most need to make sense of your own victimization by a man is for another man to get in the abuser's head and explain what the fuck is going on with him to you