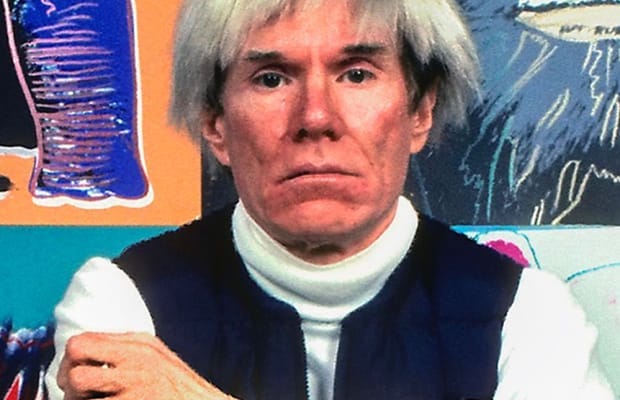

Andy Warhol, 1928–2022

A funereal party report in memory of the bourgeois-fascist downtown scene's beloved "Papa"

Andy Warhol is now dead, just shy of his 94th birthday. He died a few times before, but he’d always come back—first the Solanas assassination attempt in the 60s, and then the close call gallbladder surgery in the 80s, and then yet another assassination attempt during the Bush years. It was always so biblical, how he’d rise from the dead, each time somehow more frail and decrepit than before, to groom the next generation New York artist-socialites. But now he’s dead for good, though surely none of the cool kids at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Midtown could really even believe it—they sensed deep down that he’d pop up out of the coffin with that awkward nonchalant grin, evading questions about the miracle that just transpired, and instead of a funeral the whole thing would just turn out to be another party where everyone is wearing leather and custom black Realtree.

The Drunken Canal did a whole issue in memory of Warhol, or “Andy” as they affectionately called him throughout it. I picked up several copies at The River the night I was hanging out with Dagsen’s publicist and lawyer after we had lost Dagsen before his DJ set in the chaos of the East Village and decided to just wander further downtown. The cover was just a huge block of black ink and the headline “ANDY IS DEAD.” The only event listed under “Happenings” was the memorial service at St. Patrick’s, which is no doubt the event of the year, or at least the summer. In the centerfold there were all these pictures taken by that Cobrasnake guy of editors Claire and Gutes and their friends and Dean Kissick and Cat Marnell and Meg Superstar Princess and the musicians from the Drunken Canal’s battle of the bands at those last Factory parties and then some others, each with darling Andy. There were also a bunch of stories where these characters would tell their anecdotes about hanging out with Andy, they’d mention his wry witticisms and how he connected so-and-so with so-and-so, how he helped them sell their art, how he loved collecting their stupid chapbooks, how they’d also call him “Papa.” It was cute but it was also very corny, and it’s hard to imagine Warhol refraining from making fun of it—but I guess on some level he’d have to find it charming, since he committed his life to this sort of thing.

My own brief, virtual relationship with Warhol was a bit more antagonistic. Before I moved to New York, I had a tweet that went semi-viral calling Warhol a gay incel fascist elitist reactionary, or something to that effect, maybe with more Lacanian jargon, which he must’ve seen and been sufficiently amused by to quote tweet it with a dry “Yes.” I was somewhat starstruck by the response, but it was clear that I had been owned online, even though I was correct, and that my criticism had been neutralized by this unexpected (but totally characteristic) turn. I remember Dasha Nekrasova retweeted Warhol’s tweet and added something snippy about how I’m cringe and annoying and then I got the pile-on from the Red Scare podcast audience to really drive the point home. Warhol was a master of this sort of evasion, this “you said it not me” attitude toward his artworks and broader persona that would provoke the critics into saying more than they intended to, and then the critiques would be recuperated into the work. A survival tactic for the cutthroat discursive worlds of New York City high society and the internet. Calling Warhol the gay incel fascist elitist reactionary is then just a flattering testament to his relevance—and even though he’d repeat the same old shit, he could still shock polite society even as he offended no one, as with his trademark pop-art renditions of Elliot Rodger and his “Gun Series” (not to mention the short-lived Andy Warhol’s Million Dollar Extreme: World Peace). There is no doubt that he was one of the first people to truly anticipate the phenomenon of mass shooters and its deep death-drive connection to glamor and celebrity.

Warhol’s philosophy of love: “The most exciting thing is not-doing-it.”

Sitting in St. Patrick’s for the memorial service alone like an incel in black Levi’s, Doc Martens, and a Superdry motorcycle jacket over a black T-shirt, right behind a couple cool dumb girls talking about monkeypox wearing what can only be described as slutty mourning dresses, while the priest droned on and on taking this all very seriously, I scrolled through my emails reading the responses to my latest Substack. This one guy who’s been reading my work since the Jacobite days asked if I ever worried that I’ve been accepted “because people—especially these, who’s relevance is, in most ways, self-perpetuating, a castle in the air (the electrons of the internet or whatever)—love to see their names in print? That fame is immune to dialectical critique (especially in a seemingly popular substack) because critique still begets notoriety?” He said that he enjoyed my writing but that it feels “La Dolce Vita vibes.” I started thinking about La Dolce Vita, trying to distinguish my memory of it from my memory of 8½ and Antonioni’s La Notte, which had all formed into one big mush of Marcello Mastroianni hanging out with incredibly beautiful women in the shadows of Mussolini-era EUR district buildings and having the sorts of existential crises that cool, sexy people have. I googled La Dolce Vita and the images popped up of the intensely erotic scene where Mastroianni and Anita Ekberg are in the Trevi Fountain and immediately felt flattered, although I knew this was deceptive. I refreshed my memory of the plots of the three movies on Wikipedia: 8½ is the one about the film director with creative block making a sci-fi movie, La Notte is about the disillusioned novelist and his frustrated wife (and has the scene where Monica Vitti’s character’s businessman father offers Mastroianni’s character an executive position in his company, which always reminds me of Thiel), and La Dolce Vita is about the tabloid journalist “who, over seven days and nights, journeys through the ‘sweet life’ of Rome in a fruitless search for love and happiness.” Right, right. The guy who wrote the email asked if I felt torn between a desire for the life of an intellectual and the life of a journalist chasing the decadent hedonism of Rome’s self-indulgent aristocracy. I needed to actually rewatch the movie to answer that one, and I did so later that night. Indeed, the movie was quite relatable. (I had also forgotten Nico was in it; all roads lead back to Warhol.) Still, I can’t help but feel like Mastroianni’s character (also named Marcello) would just be happier and more psychically liberated if he was, like, more… I don’t know… communist about it all (meaning in his relationship to desire and to writing), not in the fake only-in-it-for-the-pussy way like Jean-Luc Godard (who gave up Maoism to become a Jacques-Alain Miller tier shitlib) but real communist like Jean-Pierre Gorin who actually did all the work on Godard’s “radical period” films like Tout va bien. Marcello ends up choosing neither the life of the intellectual nor the life of the journalist—but I mean, why not choose both, dialectically, who cares? Scrolling Twitter in the cathedral during Warhol’s memorial service, I saw a mildly antagonistic exchange between John Ganz and Matt Yglesias about cancel culture and PMCs and elite institutions and all that bullshit, both interlocutors with geotagged tweets indicating they’re in Italy for the European heat wave summer. Both are basically the ultimate self-satisfied Substack intellectuals, Yglesias as this demonic left-leaning neoliberal human groyper troll who comes up with rationalizations for things like the 2013 Dhaka garment factory collapse and Ganz as this anxious Brooklyn social-democrat who wants to save bourgeois American intellectual life from its inexorable descent into fascism (obviously Ganz is the less-evil one). Ganz DM’d me on Twitter the other day asking for some background for this hipster fascist downtown scene takedown piece he was writing. Jeet Heer chimed in on Ganz’s side, pointing out the irony of Yglesias tweeting from a Tuscan villa how he only cares about free speech for the elites and how the proles who use public libraries can go to hell. Ganz responded to Jeet saying “I mean I’m tweeting from Rome,” to which Jeet replied “I’m assuming you are in The Bicycle Thief and Yglesias is in La Dolce Vita.” Upon reading this I literally burst into laughter (earning the glares of some nearby mourners who were apparently listening intently to the priest), first of all at the idea of Ganz asking people to become paying Substack subscribers like he’s this hopelessly marginalized and desperate proletarian brutally beaten down by the cruel indifference of social forces beyond his control—and second, bitch, *I’m* La Dolce Vita. But back to Warhol.

Warhol had a long career with a variety of discrete periods, some more fruitful than others, but always recycling itself, especially in the later years. There was the otaku period, the 9/11 period, the grotesque studies of eating disorders and dermatillomania, there was the meeting with Žižek, the indie sleaze period with the poorly-aged Obama euphoria interlude, the album artwork for Kanye’s Yeezus that parallels the iconic Velvet Underground & Nico cover, the Grimes noise album, the “Live Laugh Love” period that ambivalently satirized the Tumblr cottagecore tradwife ideal but was also vaguely seduced by it, the terrorist chic period, the period where Warhol tried to get people to use reaction gifs of him on social media, the cultural appropriation period, the time Caveh Zahedi slithered in for the disastrous Factory reality TV show, the mid-2010s hypebeast-douche period when Warhol was enchanted by and tried to become Ryder Ripps, there was the “Ideologies” collaboration with Josh Citarella that presented ideology as a sea of nonsensical flags, there was the “Trump Series” and the time that Kantbot and Logo Daedalus briefly entered his orbit by way of Kantbot’s old college roommate who runs a downtown art gallery (Logo now posts Twitter threads about how Warhol is a CIA plant who stands in the way of achieving LaRouchian communism and unlocking infinite fusion energy), there was the time that a bunch of venture capital surfer twinks from Southern California got him into reading BAP (which he must’ve loved because he identified with BAP’s elitism and conflicting fascination and disdain toward “abjection”), the glamor shoot with Ottessa Moshfegh that people keep reposting on Twitter, the NFT collection that shamelessly repackaged all the greatest hits—and, of course, all his incel mass shooting stuff, which I’ve already written about at length in these Substack posts. Throughout all this, the icons of the Catholic Church are always popping up, but there’s no real “Catholic phase” so much as a “refrain” pointing toward an eternal confusion of the sacred and the profane that characterizes contemporary technoculture.

It's fitting that Warhol’s last project was producing the deconstructed Easy Rider remake starring Dasha and Julia Fox. It’s this final “angelicist” work that ties together all the disparate threads of Warhol’s fascist apocalypse: the pornographic e-girl Catholic network spirituality icon motorcycle rebel Americana nostalgia all comes together on the wild west settler frontier of pure surfaces, of pure extinction-machine jouissance. I offhandedly dunked on it in my Matt Gasda play review basically to say that Gasda’s plays and the Dasha Easy Rider share a paranoid-repressive sexual politics that’s symptomatic of the whole downtown world (both Catholics, they represent the opposing poles of artsy downtown Catholicism—Dasha the ditzy glamorous Warhol girl icon, Gasda the brooding Heideggerian pessimist), but I didn’t go into too much detail on Dasha’s movie, and then later Dasha DM’d me on Twitter asking, “so you didn’t like Easy Rider?” I figured that, since she had asked, it was as good a time as any to flesh out my thoughts on the movie, which I intended to review when it came out but never got around to doing. So, I told her what I thought, trying to make it sound as charitable and diplomatic as possible without taking back the shots I had already fired. The movie is promising with its funky genderbending premise—Dasha as Peter Fonda’s Captain America figure, played androgynously to evoke James Dean, or Gosling in Drive, next to Julia Fox as Dennis Hopper’s suede fringe jacket hippie outlaw, played in this contrasting breathy voluptuous sexy way that’s also supposed to be an Indian for whatever reason and is weirdly racist, but they get offended if you point that out. It’s clear that it’s an “art movie” with its long minimalist shots of bodies caressing motorcycles in the sunset, its repetitive oscillations between silence and the roaring engine drones, and the fact that it has even less of a plot than the original film, which is (rightly) seen as a mere nostalgic relic of Americana to be plundered, sampled, remixed, and so on. And then our biker rebel heroes get to New Orleans and the mood shifts to the tedious arc of religious “blessedness” with a writhing collage of cyber-icons that basically becomes an ad for Praying. And to add insult to injury, when they leave New Orleans and are ultimately killed by Amerikkka’s intolerance of true restless freedom, this scene of death—with bloodied boyish leather-jacket Dasha in delicate repose beneath primordial Earth-mother Julia Fox’s cleavage like Michelangelo’s Pietà—is implied to be an allegory for cancel culture, and the libs and President Brandon are now the real intolerant ones. What a groaner. So I told Dasha all this and tried to soften it by clarifying the context of my Lacanian-Maoist blablabla critical angle, that I’m doing a “bit” out of taking the complacent New York millennial bourgeoisie to task for not making any revolutionary art in this decadent intellectual climate that produces nothing but rich kids whining about being innocent artists aggrieved by PoCs and queer people and wokeness while the world dies. I try to be optimistic about the possibility of these people using their platforms to make non-fascist and actually-good art somehow, or at least self-aware—though this is perhaps naïve and betrays my own bourgeois background and ambitions—and they basically have to do serious “self-criticism” to get there. They don’t have to drop the Catholic thing entirely, which is oddly bonded to the Maoist discourse through Lacan and his disciples. I sent Dasha a link to a PDF of Cardew’s Stockhausen Serves Imperialism, but that was getting way ahead of myself. Out of the blue a few weeks later, she sent me an excerpt of George Bernard Shaw’s preface to Saint Joan, which included a passage harshly responding to his critics of the time. I asked her if she was implying my writing stood for the philistine Fleet Street press of a century ago, and she said no, that what she meant was just about criticism in general. And then just yesterday I got a strange bump in Substack subscribers and soon found out, of all things, that Dasha had apparently been talking positively about my writing on Red Scare. Go figure…

God knows what all the Dashas of the world will end up doing without their Andy, who was not only a person but an institution, in the sense that the nuclear family is an institution. Warhol’s real work was the party, the social scene, which started in the loft. This was the space for an alternative ordering of society, one that rejected the stable couple and the positivist idealization of occupancy, but that also didn’t seem to call for marginalization, or affirming a revolutionary ideological project, or really any renunciation of the pleasures of capitalism. But transforming the eccentric aesthetic of the loft into the spatial concept fit for upper-class consumption also means the demise of the ludic bohemian utopia. If AIDS didn’t get you then the skyrocketing rents certainly would. The “downtown scene” of today relates to the downtown scene of the 70s and 80s like colonists wearing the ornamental garb of the indigenous peoples they conquered generations ago. Saint Andy held the illusion together—through him all us New York artist-socialites could partake in the sacred rituals of Lou Reed or Jean-Michel Basquiat or Keith Haring or whoever, just like how the ministry of the Catholic Church is derived from the apostles through a continuous succession. And now what’s left? A lot of vacant real estate bought up by absent Chinese billionaires, the Thiel and Yarvin parties, NFTs, young professional banality, Gasda’s theater, a few cramped bars at Dimes Square, fashion zines that talk about Spengler, fentanyl bumps, hundreds of failed autofictions, and the slow collapse of all our youthful pre-political dreams into endless apocalypse.

NATO Faggot.

I think that scene would really benefit from a Warhol figure. Many of us were involved in the edgy downtown NYC scene pre Dimes Square, Red Scare, Yarvin, etc. The music was more like neofolk, noise, experimental, and industrial. A lot of this was inspired by the no wave scene with bands like Lydia Lunch and Sonic Youth. It was all very “cool” and while it wasn’t reactionary it was definitely not woke.

Petty gossip and media pieces don’t grow a scene. You need actual artists, devoted musicians, and performers who are ready to unleash it all. If Dimes Square gets a Warhol, that kind of thing will be possible, and we will be looking at a true vibe shift that influences future generations and not just an insular scene.